Democracy on Mars 3: New Tools for Popular Sovereignty

Note: this is the third post in a series. The earlier posts are here and here.

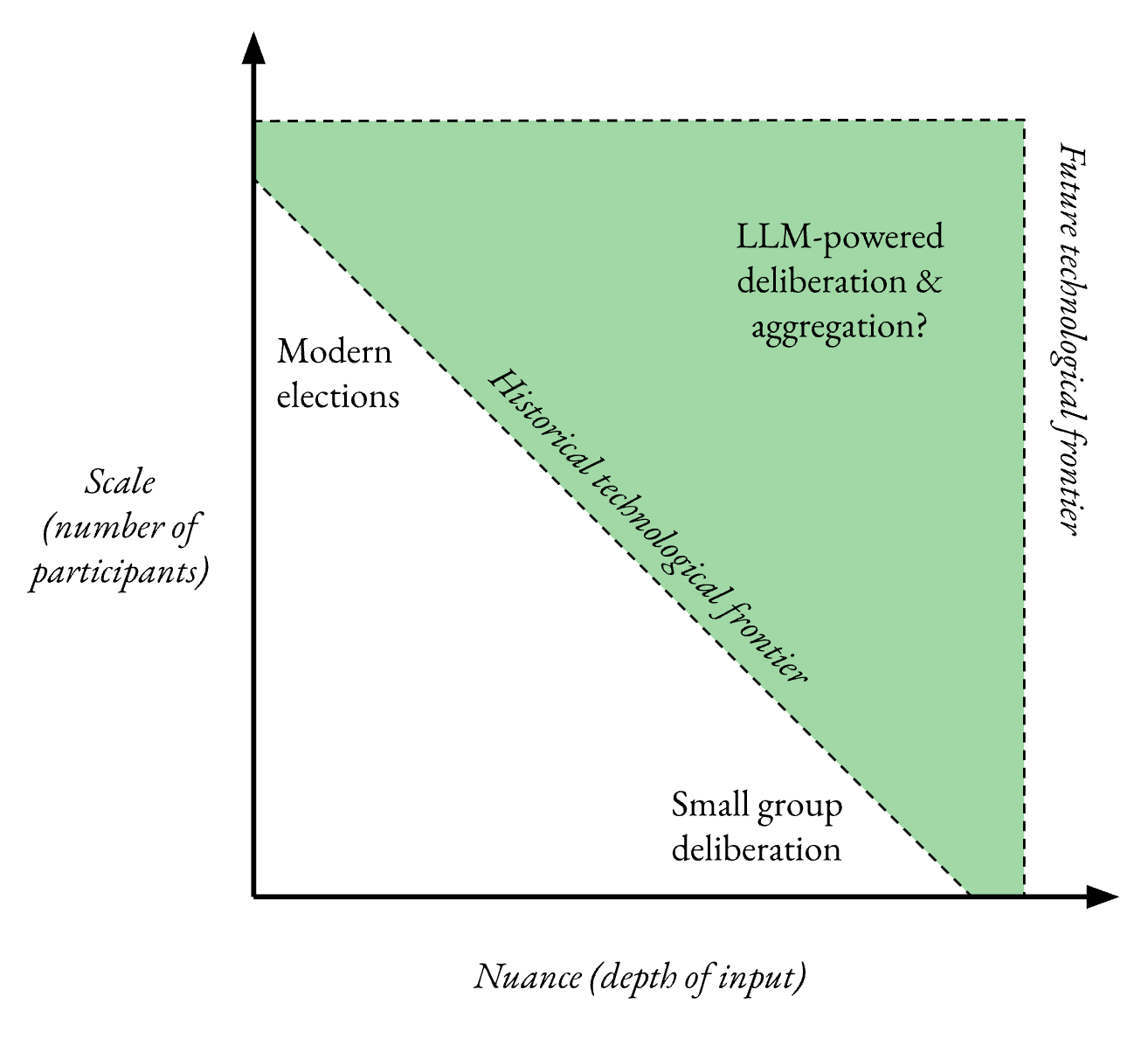

Martian system designers, no longer tethered to the logistical constraints of prior centuries, could pursue democratic ideals in new ways. Some of the most interesting and philosophically provocative of these options are platforms that could relax the informational bottleneck that has limited large-scale decision-making.

AI models that ingest and aggregate natural-language input from an unbounded number of participants could free citizens from the confines of the ballot. Pairing these with the ability to store and instantly share arbitrarily large amounts of data could facilitate more frequent, responsive and light-touch opportunities for input. The Martians could replace today’s regular electoral cadence with organic opportunities to influence high-impact decisions in near-real-time.

In a best-case scenario, these innovations might make democracy feel to the Martians like a rich, ongoing conversation – the kind of atmosphere we associate with small, tight-knit groups – as opposed to the sparse, formalistic interactions that dominate contemporary terrestrial democracies (ballots, petitions, lawsuits, etc.). In more pessimistic scenarios, the same innovations could entrench bias and reduce interpretability. In any case, they would have complicated higher-order impacts that cannot be fully anticipated and pose fundamental philosophical questions about what people really want from government.

The goal: nuance at scale

Humans use language – the primal social technology – to break complicated issues into subtopics, acknowledge uncertainty, highlight tensions, and bargain. Anyone who has had to plan a trip with friends has seen how free-form discussion can find its way to a decision: people have all sorts of constraints and preferences (budget, timing, connectivity needs, dietary restrictions, etc.). A short conversation can identify and separate these threads, enabling far better optimisation within the high-dimensional space of possible activities than, say, trying to address the same questions through a series of ballots. In government, both the pre-ballot selection of candidates and post-ballot decision-making processes typically rely on deliberative methods, and a growing appreciation of citizens’ assemblies reflects the value that similar conversations can have for the general public.

Unfortunately, deliberative conversations have historically been hard to pull off with more than a few dozen people, especially if one wants to ensure that all voices are heard equally. Ballot-based voting, for all its weaknesses, has long been the least-bad option for democracies because it can scale to millions of participants and offers a well-defined, enforceable metric of equality—one person, one vote.

The Martians, however, could replace ballots with rich conversations at scale, facilitated by AI. A ballot asks “which of these options do you prefer?” It does not ask why, or what you hope they will do for you, or what—among the many promises associated with a given candidate or policy—you might be willing to give up to gain something else. It also does not ask if this is an opinion you have held for a long time based on expertise, or one that you settled on this morning because of a recent event. Systems such as large language models (LLMs), on the other hand, could engage the voter in extended conversation, elicit complex preferences, then synthesize this and aggregate it with similar input from others.

At their simplest, personalized AI tools could learn to predict a given individual’s response to particular prompts (“do you support this policy?,” “which candidate is your favorite?”). A more ambitious vision with both greater potential gains and larger risks would involve training models to serve as personal voting consultants (AI-as-advisor).

Personal voting advisors

AI systems such as LLMs could elicit rich and detailed preferences, helping voters make informed decisions about policies and candidates.

AI tools could absorb voters’ detailed political views via conversation and help them make informed decisions. An AI advisor could guide voters through a process to figure out what they actually want, then map those desires to specific policies or candidates.

People have contradictory political desires for a host of reasons, including innate value pluralism, an unwillingness to confront trade-offs, and/or empirical misunderstandings that lead us to misconstrue the likely effect of policy interventions. Consider someone who wants lower taxes along with improvements to local schools and public services. Identifying tensions between these goals involves analysis of relevant data and academic literature, and assessing what trade-offs one would accept requires introspection. Today this is rarely worth voters’ time, and politicians benefit from peddling panacea narratives that sweep nuance under the rug.

AI, however, could not only offer everyone an expert personalized assistant steeped in relevant research, but also a political therapist capable of engaging users in a reflective-equilibrium-like process to untangle conceptual threads. Rather than simply query initial intuitions, it might ask about higher-level principles (beliefs about the relative value of freedom and security perhaps), and talk them through assumptions or contradictions in their thinking. Through these exchanges, voters could reach refined, all-things-considered opinions, which the AI systems could use to recommend policies.

As a parallel, consider that when people – especially the wealthy – make consequential decisions in complicated domains, they often enlist the help of experts to walk them through trade-offs. Someone seeking medical treatment might want a non-invasive solution with fast recovery and few side-effects, and it may fall to their doctor to explain that these goals are at odds with one another, to tease out exactly how much each one matters to the patient, and to make a recommendation based on a holistic, reflective weighting of priorities. Investment advisors, architects and myriad other professionals play similar roles. Policy is just as complicated as these domains, but we rarely have this kind of support available.1 AI could change this.2

Though the end goal is advice on policy choices, voters would not have to “speak policy language” in order to engage with these tools. They could express their desires at any level of abstraction and specificity, ranging from complaints about potholes to reflections on positive and negative liberty. A capable system would meet each user where they are and work with them to achieve clarity on what they want to see in the world. This might be as dry as sharing political science papers, or as immersive as giving users a visceral feel for how particular policy changes might affect their daily routine. Such systems might employ data visualizations, generative imagery and video, or even simulations in virtual reality.3

Offering this kind of tailor-made policy research could answer a persistent critique of democracy: the millennia-old argument that the general public is not equipped to grapple with the range and sophistication of considerations one must master in order to cast an informed ballot. Restricting voting to those “in the know” is undesirable in a democracy—it strips away critical information about the values held by the population and exacerbates incentive misalignment by giving elected leaders little reason to heed much of the population. Even voters who are less informed about policy know a great deal, in particular about their own lives, needs and desires. The challenge for democracies lies in translating these perspectives into something legible to the policy establishment. Proposed mechanisms such as futarchy aspire to separate voter values from empirical beliefs on the premise that the electorate can be trusted to convey the former but not the latter. But moral and factual considerations are persistently entangled in human minds, and extended dialogue may be the most reliable way to get to the bottom of what informs a particular conviction.4

Systems that have extracted detailed preferences from voters could put that knowledge to work in many ways. The most straightforward path is simply to help voters with the research and compression tasks required by today’s political structures (filling in ballots). But these systems also open the door to more radical proposals, as explored in the subsequent sections.

The use of LLMs for these purposes also carries obvious downsides, most notably in terms of interpretability and fairness. It’s easy to imagine such tools manifesting bias in ways that are invisible to users – for instance, recommending a preference synthesis for an individual that’s not in their best interest, or producing worse suggestions for people from marginalized groups. This could happen as a result of tampering or just lack of foresight. Difficulties may lie at the level of implementation or extend deeper because a clear metric of quality may be lacking even in theory: where is the line between helping someone confront contradictions within their own thought (which is generally useful) and actively persuading them to adopt new views? At what point does personalization – for example, using varied terminology to describe the same idea to different users – transition from helpful to discriminatory? Recent AI history is full of alarming practical failures (e.g., releasing products that turn out to be racist) and deep theoretical quandaries such as impossibility results, and LLMs in particular pose all sorts of challenges.5 Machine learning systems are far more expressive than ballots; this brings opportunities while also greatly expanding the number of failure modes that designers have to take into account.

Even supposing that Martian designers arrived at a clearly defined and universally palatable set of desiderata for a preference-elicitation-and-refinement system and developed an exhaustive set of training and evaluation methods, would the Martian public trust it? Political infrastructure on Earth routinely comes under suspicion (sometimes warranted) of corruption, and presumably adding further technical sophistication would increase these concerns. But perhaps this is the wrong angle of analysis – maybe the takeaway from related episodes on Earth is that our comfort with complicated technical tooling depends more on general societal trust than on the innate technical aspects of particular systems.6 This would suggest not that the Martians shouldn’t deploy advanced AI-enabled political decision-making aids, but that they have to bear in mind that such tools do not exist in a vacuum and can only function in the context of other ingredients such as civic and technical education.

Frequency and granularity

The Martians could elicit public preferences far more often, including in more precisely-scoped ways.

A simple way to integrate language into existing electoral templates would be for participants to have a conversation every few years with a tool that provides personalized advice on how to complete the ballot for that election cycle. But the old Earthly pacing and structure is grounded in logistical constraints that no longer apply, and Martian designers could innovate in a number of ways, all of which bring distinct trade-offs.

On Mars public input need not be limited to biennial or quadrennial election group events. It could occur more frequently and in ways that impose less of a burden on participants, allowing citizens to render verdicts on policy initiatives or politicians’ performance in something closer to real time. With today’s information storage and networking technologies, the Martians could build accessible, “always-on” electoral infrastructure. They might construct a network of pervasive, secure, dedicated machines (not connected to the public internet) that use both paper and electronic auditing, making voting as easy as withdrawing cash or buying a coffee. Pending cybersecurity advances and sufficiently robust identity verification platforms, Martians might be able to vote via personal devices.78 (To be clear, internet voting is almost definitely not advisable using contemporary capabilities).

This voting infrastructure, in combination with language-based ML systems, could enable the Martian public to issue finer-grained guidance than Earthlings do: instead of just selecting representatives and weighing in on the occasional, vaguely-worded referendum, people could vote on specific legislation in the spirit of direct democracy. Historically this has been infeasible without imposing a massive research burden on participants – a challenge that has only grown as the world has become more complex and government responsibilities have expanded – but ML tools that map people’s all-things-considered preferences onto policy options can lower that cost.

Allowing for short-notice public engagement opens the door to a more dynamic interplay of current events and democratic input. Absent crises such as the collapse of a government, most Earthly elections occur on a regular timetable and/or at the choice of the ruling party. A case can be made, however, for a more responsive electoral schedule. Arguably, different circumstances – economic tumult, armed conflict, technological upheaval, etc. – call for different pacings of engagement. In some situations voters may be happy to let the government trundle along for years at a time, while in others they may want to take the wheel.

Would Martians enjoy such frequent engagement? Most of us can’t be bothered to fill out online surveys, and current systems that make room for voluntary input are often captured by wealthy incumbents – how many people would really relish the opportunity to provide more frequent policy guidance, even if doing so could be made less annoying? As Oscar Wilde supposedly said, “the trouble with socialism is that it takes up too many evenings.”

One possibility would be more frequent touchpoints, freed from the participation expectations of today’s marquee political contests – opportunities for weighing in that people could take or leave.9 This might take a liquid democracy form, in which voters modulate at will between direct voting and outsourcing to a trusted intermediary, while resting assured that, in one way or another, their interests were represented.10 In situations that prompt us Earthlings to write editorials, call legislators, or take to the streets, Martians might simply reclaim direct voting rights.

A truly adventurous system designer might travel even further along the road of replacing interpretable but limiting and mechanical systems with richer but less comprehensible machine-learning powered alternatives.

Personal political representatives

AI could write policy directly, bypassing the constraints of the ballot.

In all of the above scenarios, the final interface connecting individual opinions to government action remains constrained by the choke point of the ballot. AI advisors may help inform individuals’ choices and enable them to provide input on a broader array of policy particulars, but agenda-setting – the decisions about what appears on the ballot – still sets the terms of political decision-making via processes inaccessible to most voters. Participants choose from a handful of discrete choices that may lie very far from their ideal outcome, and the compression of the ballot destroys the detailed preference information the AI has absorbed.11

One alternative to the AI-as-advisor model would bypass ballots and incorporate AI directly into the policy-making process (as opposed to just the policy-choosing process). Under this model, AI systems would bind outcomes to voter preferences by writing policy based on the underlying representations gleaned from conversations. These personalized AI tools, rather than just helping voters reach an informed decision from a discrete slate of options, would collectively explore the much higher-dimensional space of possible policies, optimizing for some measure of collective well-being. Every word choice in every law could, in theory, be traced back to an aggregation of the detailed preferences of the masses.

At its most radical, such a system might wholly replace human representatives. A reductive description of the role of legislators is that they take a popular mandate – such as their own election or the public selection of a referendum option – and convert it into policy. AI may be able to perform this function more effectively. A less extreme path might keep human representatives in the loop to sign bills into law formally and to veto draft legislation that seems especially flawed. In any case it is conceivable that AI would play a role closer to that of a representative or advocate than an advisor.

This AI-as-representative approach would fully eliminate the informational choke point of the ballot and the power of agenda setting. One way of thinking about such a scheme is that every voter would be represented by a personal entity intimately familiar with their preferences, more knowledgeable about every area of policy than any human, and committed to working 24/7.12 These entities could engage in depth with one another via simulated deliberation at a scale far beyond anything humans can undertake. And whereas human legislators vary in their clout and effectiveness, leading to inequality of representation, a system of AI representatives could guarantee every voter equal bargaining power. They could also make decisions in real time while remaining grounded in public preferences, in contrast to the tradeoffs created today by time-consuming public comment periods or referendums. Cesar Hidalgo and Bruce Schneier have outlined proposals along these lines.13

The more frequently a user provides input to such a tool (statements that could be as local as “the traffic at this intersection is always terrible” or as global as “I can’t believe we aren’t devoting more resources to helping Earthlings fight climate change”), the better the system could take their interests into account. Some Martians might go further and grant their virtual representative access to personal information to enable better modeling of their preferences without requiring explicit guidance: this could include public data such as social media posts or, more intrusively, location services or biometrics that reveal whether a new bike lane has affected the user’s daily commute, REM data that indicates how much a nearby construction site disrupts sleep, and so on.14 (Yes, this sounds invasive and terrifying. More on the risks later.)

Communication with representative AIs could be a two-way street. In addition to absorbing information about preferences, these systems could keep voters apprised of why and how decisions were made, explain when outcomes diverged from forecasts, and give individuals a sense of how their opinions compare to those of others.15 These updates could be customized to match each individual’s preferred frequency and format. Such tools could even arrange and mediate discussions between voters on political issues (as described in the next section).

Under a reductive view of democracy as a mere preference aggregation system aiming to generate the greatest average utility for participants, the AI-as-representative approach goes a long way towards realizing democratic ideals.16 From an information-theoretic perspective, current systems involve exceptionally lossy compression, and deeper and more frequent input could mitigate this shortcoming. But most democratic theorists would agree that this conception is at best incomplete (and at worst, actively misleading): democracy is ideally a process that brings communities together, creates a common sense of identity, imbues participants with mutual respect, etc. An AI platform that deals only with atomized individuals and aggregations thereof is missing something.

Democracy as discourse

AI could contribute to democratic health not just by eliciting and aggregating preferences, but also by facilitating large-scale, respectful deliberation between community members.

Beyond serving as research assistants and preference aggregators operating in service of isolated individuals, AI systems could form a new kind of social infrastructure that brings people together virtually at a previously impossible scale, identifying areas of common ground, increasing empathy for those with divergent opinions, and building intra- and inter-community ties. Pol.is, a platform that enables users to respond to prompts via natural language and voting, and then groups these statements to find areas of maximal agreement, represents a step in this direction. Recently, machine learning research conducted at DeepMind and by a team at Anthropic in conjunction with Pol.is has shown that large language models (LLMs) can perform similar functions. Scholar Hélène Landemore has written about this as well.

AI tools could increase not only the scale of deliberation, but also its quality and empathetic potential. Machine translation, for example, could enable real-time deliberation between people who don’t speak the same language. Similar models could provide “viewpoint translation,” reframing a statement in language more relatable and accessible to specific voters (for instance, employing personalized metaphors to explain new technical concepts).17 These systems could offer real-time fact-checking and synthesize relevant research on-demand when participants encounter an empirical crux. By incorporating best practices associated with citizens’ assemblies, such tools could create spaces in which people feel comfortable and respected. We have become used to social media platforms that foment conflict, reductive argumentation and sensationalist claims in order to maximize engagement, but this is not an inevitable feature of scale: bridging-based systems can harness the same underlying insights to produce the opposite result.

The result: a constant conversation

Together, this combination of AI and modern digital hardware could produce an ongoing, layered conversation among Martians and between them and their government. Above and beyond abstract traits like greater information throughput and higher-quality policy outcomes, this form of engagement might feel meaningfully different from democracy on Earth. Elections today are formal, mechanistic rituals. Connecting with the state via petitions or legal action requires forms, lawyers, resourcing, and familiarity with a set of social codes and professional vernaculars that are inaccessible to all but a small elite. (Unsurprisingly, these sorts of elective political engagement tend to skew towards the already privileged.)

Perhaps counterintuitively, emerging technologies might enable a return to the casual feel of local democracy – friend circles, student clubs, reading groups, religious communities, sports leagues – where we regularly voice input informally. Obviously something operating at a national (or planetary) scale won’t feel quite like these cozy environments. (Assuming human social bandwidth remains where it is now, for instance, the Martians won’t be able to know millions of compatriots the way people know next-door neighbors.) And yet AI-powered tools, for all their sophistication and opacity, might make the world of policy – and collective decision-making more broadly – feel less mechanistic, industrial and alienating, and more intuitive.18

By way of analogy, much of the history of computer user-interface (UI) design, such as the migration from terminal to graphical interfaces, can be framed as getting computers to speak human language so that humans don’t have to speak computer language. This has often involved developing technical tooling that abstracts away low-level operations, enabling people to specify outcomes in the ways they find most comfortable. AI holds similar potential for many domains, including the policy space. Much as LLMs today enable people with no coding experience to write computer programs by simply describing what they want to create, or to produce essays in a language they’ve never studied, future models might empower voters to think through the world they want to live in, and craft policy that increments in that direction, without having to acquire new expertise.

At the same time, of course, these could go badly wrong. The possibilities surveyed above increase dramatically the power of automated systems that do not offer the kind of interpretability that today’s voting mechanisms do. There are enormous cybersecurity risks because these models could become centralized points of failure (always a bad design choice), and testing and debugging ML systems remains poorly understood. Even assuming these technical issues can be solved, there are moral and political questions around aggregation: what are these systems trying to achieve? Adherence to the preferences of the median voter, optimizing for mean welfare, enacting only policies that enjoy widespread consensus, or something else? In aggregation, as in fairness, no system can satisfy all desiderata. This hasn’t stopped us from voting on Earth, and it need not on Mars, but Martian designers will face choices with serious trade-offs. The later section on “Philosophical questions” explores some of the most compelling of these issues.

Next post: New tools for state capacity (still under construction, the linked page is a preview)

There are plenty of online tools that offer to suggest candidates based on ideological positions (some of which even enjoy widespread trust), but these generally are structured as surveys – a format that people find boring and which does enable personalized insights as thorough as something based in natural language.

One important difference here is that such systems would not aim to “sell” users on particular packages, but to provide realistic, relatable and informative depictions of possible futures.

Employing a range of methods to communicate the likely effects of policies could also get users to step back and consider larger, systemic problems (and solutions) than the kind of political issues that typically dominate headlines. This could help avoid people getting stuck in local minima/maxima. However, these possibilities also raise questions about what “all-things-considered preferences” really mean, and at what point a system meant simply to inform users begins actively persuading them. I discuss this in detail in the section on “Philosophical questions.”

This distinction between the desirability of future worlds and the policy tools necessary to achieve such possibilities largely mirrors some AI alignment/safety research which focuses on extracting preferences separately from applying a “world model” to determine appropriate interventions. The Open Agency Architecture captures this split nicely. As a side note, AI systems could also offer new and powerful contributions on the “world model” side beyond merely synthesizing prior research. The upcoming section on state capacity describes ML’s strong track record at predicting the behavior of complex systems, and its potential to tackle the kind of social scientific problems that undergird policy debates.

For more on impossibility results related to algorithmic fairness (proofs that some forms of fairness cannot be satisfied simultaneously), these three papers are a good start. See this paper from Weidinger et al. on the general risks posed by LLMs, and this paper specifically on political bias.

This fits into a rich history of societal relationships with new technologies. There are plenty of tools that we mostly use unthinkingly today – planes, microwaves, computers – while others (e.g., vaccines) have become the target of politicized suspicion.

There are equity issues here, since smartphone usage varies significantly by income, both across and within countries. But as a reminder, the subject of the thought experiment is a very well-resourced Mars: the question is not “could this work if rolled out on Earth today?”, but “with capabilities that will exist soon, could we build a society where this worked?”

Expanding options for frequent engagement has equity implications. On Earth, most forms of elective political engagement, e.g. contacting representatives, organizing protest, etc., bias towards wealthier, whiter groups. Baking optional engagement more formally into the policy process could, absent effective mitigations, exacerbate unequal outcomes. However, the Martians could to some extent mitigate this via careful weighting and sampling (similar to techniques used by pollsters) and/or compensating people for contributing. These possibilities raise questions about what types of equality and equity we care about – a topic discussed in detail in the section on “Philosophical questions.”

Although outsourcing representation always brings a risk, as under today’s systems, that representatives either don’t know much about constituents’ views or choose to override them.

This isn’t to say that there’s no way for representatives to approximate this information. They can conduct polling, speak with constituents, etc. But that information does not bind the same way that voting does. (A dictator is also free to conduct polls – and many autocracies worry deeply about the threats to power that could result from public dissatisfaction – but this doesn’t imbue them with democratic accountability.)

Another minor benefit to shifting from the advisor to the representative model: systems in the latter category could access classified information, making the decision that a voter likely would make if they could read such material.

This to some extent can address the risks of uninformed public decisions: a yes/no vote on a complex policy topic is probably not the right level of question to ask citizens to grapple with. Similar proposals have gone under the terms “voting avatars” and “virtual democracy.”

All of this creates huge privacy issues, some of which are new and some of which echo existing questions regarding digital services: how can one guarantee that such data is used only for its intended purpose? How can one ensure that users feel comfortable with the eventual impact of such data? Etc. To some extent, structured transparency tooling such as homomorphic encryption, secure multi-party computation, differential privacy and federated learning can mitigate these risks, but this technology is not yet ready for widespread deployment. A future essay will specifically discuss the governance implications of these techniques, in particular the ways in which they might alter public willingness to tolerate certain forms of surveillance.

This raises questions related to transparency and interpretability: is it even possible to offer humans a deep understanding of how a neural net made a particular decision? I think a lot of this boils down to different definitions of interpretability, and I address this issue in the section on “Philosophical questions.”

Here I am using “utility” in the broad sense of “preferences over future states of the world” (i.e. consistent with VNM utility) which can take into account all sorts of factors that hedonic utility usually excludes, such as religious or moral convictions.

Nicole Doerr describes a similar concept under the name “political translation.”

One critical difference between AI-enabled natural-language deliberation/preference aggregation and casual conversation is that the former offers opportunities for measurable, enforceable equality in terms of how heavily each person’s input is weighed. Casual conversations can often be dominated by forceful personalities, and social norms can end up systemically undervaluing the perspectives of people from marginalized groups. In theory AI management of these conversations could offer a path to mitigate or eliminate these inequities, although as noted earlier, different definitions of fairness can conflict with one another, so designers would still have to make consequential decisions about which metric(s) to choose.