Democracy on Mars: Red Sky Thinking

A thought experiment:

Humanity is readying its first crewed mission to Mars. We have developed robust habitat modules, automated mining, extra-terrestrial agriculture and so on—all the groundwork for a small, self-sustaining civilization that might, in time, expand to billions of people. The settlers-to-be, a representative cross-section of humanity, enjoy sophisticated technology, a generous budget, and the autonomy afforded by tens of millions of miles of separation from Earth. How will they govern themselves?

The red planet is terra nullius, a constitutional blank slate. We have not faced such a scenario for centuries, during which time the tools applicable to governance have multiplied.12 We now have communication infrastructure that enables large-scale, real-time feedback; a host of sensor capabilities that could monitor the natural environment, human activity and public sentiment; the scientific knowledge and computational power to model and manage complex, previously intractable processes; and myriad new avenues for deploying force, including the capacity to destroy civilization in the span of hours.

Earth-bound governance architectures have adapted to these realities, but in a piecemeal way: politicians have social media accounts and improved polling, dedicated agencies have remits to harness new capabilities (e.g., cyber) and tackle new problems (climate change, etc.). The state now occupies a more expansive role in society than it used to. The bones of government, however, have stayed the same; almost all of today’s nation-states hew to structures designed centuries ago.3 In representative democracies, this generally involves the citizenry filling out slips of paper every few years and then leaving an amalgamation of legislative, executive and judicial bodies to go about their business, mainly by writing down rules in natural language and, later, debating how the contours of these discrete, compressed codes map onto the continuous, high-dimensional thrum of reality.

In this thought experiment, imagine the Red Planet unburdened by precedent and able to consider the full possibility space of governance architectures unlocked by contemporary technology.4 What opportunities do they have that earlier nation-builders lacked? And how could new tools better realize a democratic vision?

On this blog, I plan to examine how emerging technologies, in particular AI, could change democratic systems for better and worse. I also hope to explore a few other philosophical issues related to AI.5 In this opening series, I have two main points:

Emerging technology could both expand state capacity and increase public oversight of government decision-making. Balanced progress on these two fronts could deliver governments that are both more competent and more accountable. Enlarging state capacity without a matching increase in oversight opens the door to autocratic abuses of power, while the inverse leaves opportunities for improved government performance on the table. I call the balance a “popular sovereignty ratio”: the amount of binding guidance the public exerts over a government (through elections, referendums, etc.) divided by the collective importance of the decisions the government makes on the people’s behalf. This ratio has decreased in many democracies over time as state capacity has grown while institutions for public input have remained static. Emerging technology could either exacerbate or reduce this deficit.6

These possibilities raise deep political philosophical questions, some of which are novel while others date back millennia. Future technology could mitigate longstanding democratic tensions – for instance, between the richness of public input and the scale at which it can be collected, or between making decisions quickly and doing so in a representative way. But these opportunities create other questions, such as what kinds of interpretability are worth sacrificing in exchange for improvements in efficiency; whether public decision-making should prioritize the experiencing or the remembering self; and to what extent the wishes of the dead and the interests of future generations should guide policy. Modifications that might at first seem unequivocally good, such as letting people state opinions via more expressive means than ballots, turn out to be complicated. Conversely, some interventions that initially feel dystopian might prove more humane and desirable on further analysis.

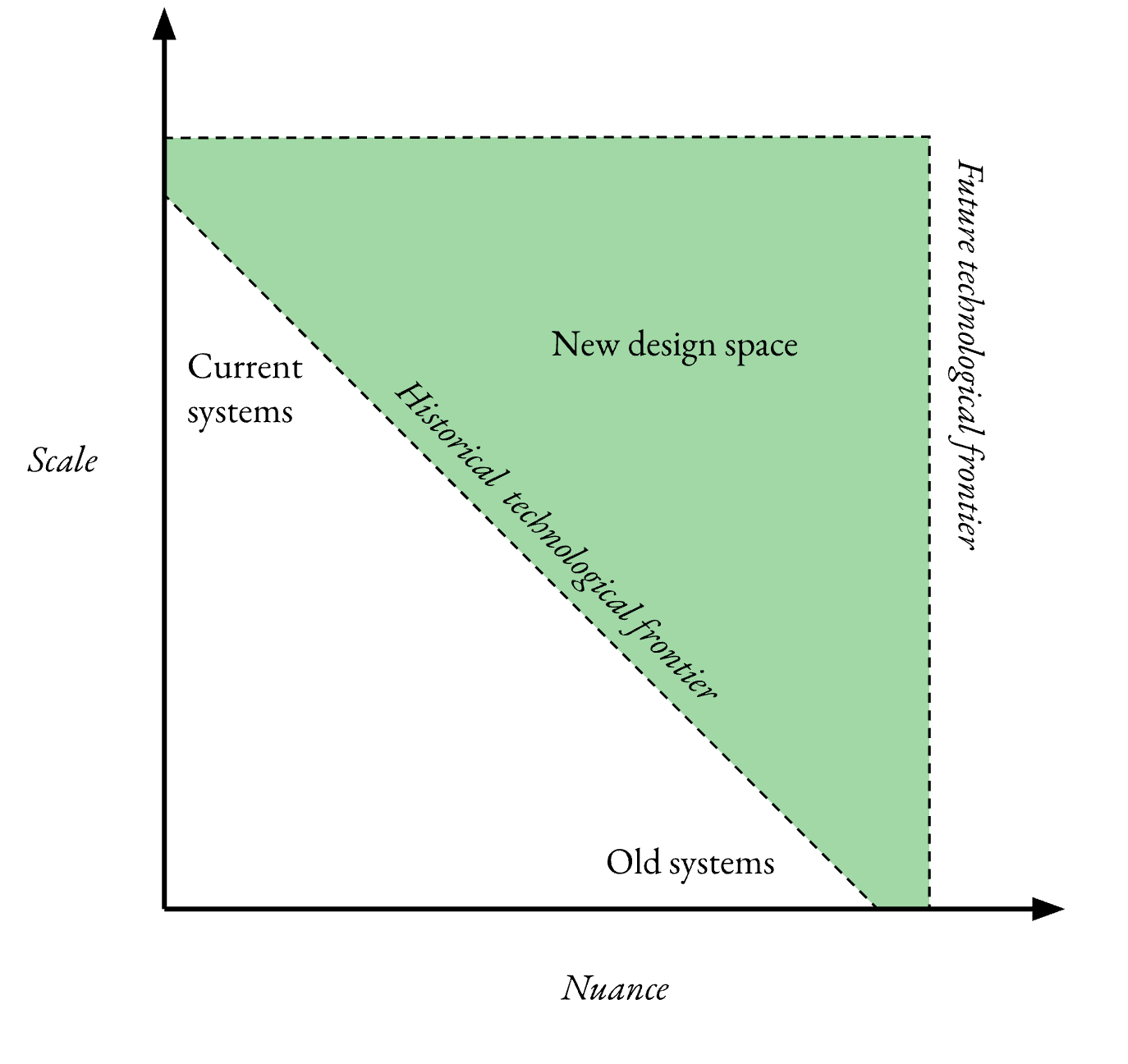

One persistent theme throughout these essays will be the conception of machine learning as “scalable nuance” – the ability to replicate, at potentially limitless scope, solutions that previously could previously only be applied very locally.7 ML’s major successes have come about in tackling problems that refused to yield to the reductionism of conventional programming and which as a result frustrated attempts to address them in a scalable way. In many of these domains – ranging from settings as rich as the game of Go to tasks as prosaic as recognizing faces – humans have long had the tacit knowledge needed to excel, but we have struggled to encode this in a way that others (humans or machines) could easily replicate. As a result, we historically faced a trade-off between techniques that could scale easily (for instance, simple, rule-based Go strategies) and nuanced expertise that was costly to learn (mastery of the game). Machine learning, however, has in many settings captured this tacit knowledge, allowing us to have our cake and eat it too.

In governance contexts, the equivalent of tacit knowledge takes the form of rich local interactions that nation-scale social technology cannot replicate: for instance, the repeated, wide-ranging conversations through which members of small groups get to know one another’s preferences in far more detail than any series of ballots could capture. ML-created opportunities for scalable nuance include “voting via language” (systems that could engage an unbounded number of people in deep dialogue) and encoding rich, contextual norms too subtle to be captured by formal law. These applications wouldn’t represent the transition to a brave new world, but rather a return to mechanisms that predated the high modernist state, albeit this time at unprecedented scale. I illustrate this concept in different settings with diagrams like this:

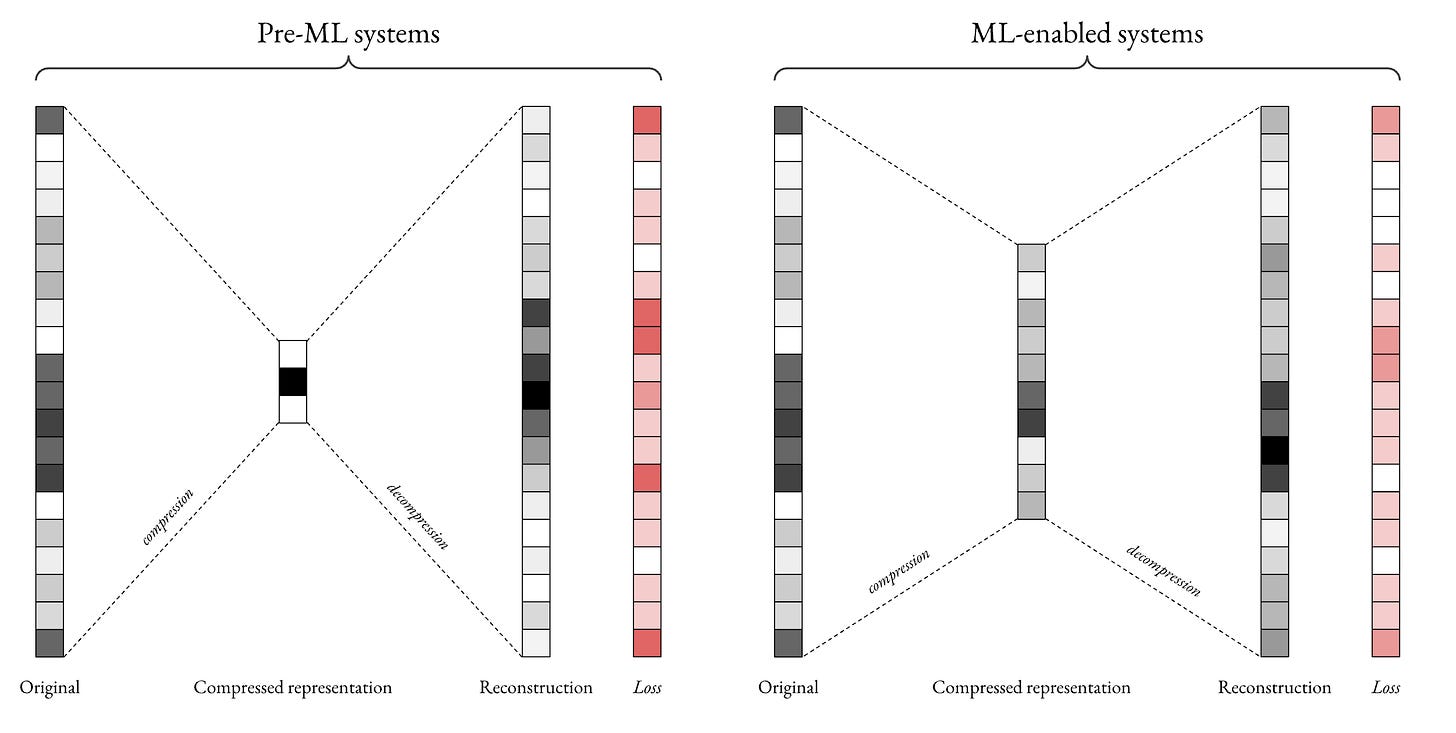

I pair this framing with analyses of today’s social systems as forms of lossy compression (meaning that they destroy a lot of information). For instance, filling out ballots and writing laws involves taking rich, high-dimensional normative beliefs and squishing them down into parsimonious representations that lose a lot of nuance.8 This creates challenges when actors have to decompress these representations – i.e., when policymakers try to make sense of the mandate given to them by voters, or when judiciaries interpret vaguely worded legal codes. These informational choke points were historically necessary due to the lack of scalable tools for capturing content in richer, more contextual ways, but machine learning shows promise for avoiding this trade-off. I visualize this idea of informational choke points with diagrams like this:

My aim is to explore a set of technological capabilities, many of which will probably sound alien, but that may be feasible within the next 50 years. These capabilities will unlock governance options previously not available to us. Some of these might be good and serve the ends of democracy, some might be catastrophic. Although I linger on reasons the Martians might find these new possibilities appealing, I am not advocating for techno-utopianism or a particular path of adoption. Instead, I hope to highlight the counterintuitive interplay between technical, philosophical and policy considerations that the architects of future governance systems may confront. This is all speculative, blue (red?) sky thinking.

Disclaimers

I don’t claim originality. Many of the ideas proposed here have been around since the earliest political philosophy. Others are relatively new, but other people have also written about them.9 I’ve done my best to find and cite related work, but if I’ve missed appropriate attributions, please let me know.

I’m assuming away some technical problems. The potential futures I outline lean heavily on AI. Many AI systems today suffer from shortcomings (hallucinations, data leakage, bias, etc.) that would make them very unreliable in application areas I discuss. I’m optimistic that many of these issues can be solved in the coming years/decades, so for the purposes of the thought experiment I assume that we’ll have better tools. There are also deeper issues that I don’t expect will have purely technical fixes, such as interpretability shortcomings, trade-offs between types of fairness, and so on.10 I try to flag issues in this latter category explicitly as I go, and much of the “philosophical questions” section concerns these topics. To make these categories concrete with two examples: I assume that we will eventually be able to trust AI systems at least as much as we would trust an excellent human research assistant (i.e. we can assume that these tools aren’t fabricating facts or quotes), but I do not assume that ML systems will offer mechanistic interpretability of the type that we associate with previous software paradigms.

I use a reductive model of democracy that is missing a lot. I focus almost exclusively on formal institutions such as voting and lawmaking, and neglect other important aspects of democracy such as media coverage, citizen advocacy and protest, attendance of town hall meetings, union activity, correspondence with legislators, etc. I also look at these institutions largely through the lens of how effectively they capture and implement preferences, but there are lots of other functions that governments – and democracies in particular – perform. Plenty of factors aside from informational efficiency (perceived legitimacy, interpretability, etc.) inform system design. For many reasons, we may want to stick with the tools we have today even when high-tech, less-compressive alternatives are available. I do my best to explore these issues in later sections. I hope that in the context of this piece – which is trying to make a few specific points, rather than present an all-encompassing account of good governance (see next disclaimer) – these oversights aren’t disastrous. I also try to address some of these issues as I go, and I dive into a few of them in detail in the section on philosophical questions.

The thought experiment ignores problems of incumbency and power imbalances. Many issues with today’s political systems persist not because we lack the tools to build something better, but because these flaws advantage those in power. This essay series doesn’t grapple meaningfully with questions of how to effect political change, which many people would (reasonably) argue lies at the core of politics.11 Later, in the section on “Philosophical questions,” I dig into other shortcomings of the thought experiment as well as questions of to what extent technology can address otherwise-deadlocked social issues.

I’m not arguing that technical progress will solve all political problems, nor that exploring/implementing these approaches is the most important line of political work. Related to the above point, there are lots of ways that people can improve democratic health and government efficacy without resorting to AI-powered preference aggregation or any of the other tools outlined in this series. We could make voter registration more automatic and accessible, declare elections national holidays (for countries that don’t already do this), expand polling locations and hours, and so on.

I’m not claiming that any of these use cases will be net positive. As I try to flag throughout, and especially in the section on philosophical questions, efforts to build the systems I outline could easily end badly horribly. Even technical success and an avoidance of dystopias may produce second-order harms that exceed the impact of the initial benefits.

Further posts in this series

The rest of this opening series unpacks the above points and is structured as follows:

Current Shortcomings (why current democratic systems are technologically constrained)

New Tools for Popular Sovereignty (ways to elicit policy-guiding preferences)

[WIP] New Tools for State Capacity (avenues for increasing the subtlety and scope of state power)

[WIP] Philosophical Questions (weird implications raised by these systems)

[WIP] Practical Questions (what putting this into practice in non-Martian settings might involve, and a discussion of ways this all might be a bad idea)

[WIP] Wrap Up

I am writing as I go, so all of this is subject to change.

Many thanks to the following people for edits: Doni Bloomfield, Ben Buchanan, Nicolas Collins, Iason Gabriel, Vishal Maini, Justin Manley, Greg McKelvey, Max Langenkamp, Anna Lewis, Emily Oehlsen, Aviv Ovadya, Adam Russell, Bruce Schneier, Jordan Schneider, Yishai Schwartz, Divya Siddarth, Allison Stanger, Susan Tallman, Luke Thorburn, Michael Webb, Glen Weyl, Jesse Williams and the GETTING Plurality group led by Danielle Allen.

The only semi-relevant contemporary examples are small parcels of land unclaimed due to complex border exchanges (e.g. Bir Tawil), and regions where no group of humans has seriously attempted permanent settlement (e.g. Marie Byrd Land in Antarctica), none of which are viable candidates for serious governance entrepreneurship (although some have tried). Ignoring colonial legal fictions that falsely claimed terra nullius status for clearly inhabited geographies in order to create a pretext for colonization, the past few centuries contain only a few examples of encountering substantial unsettled territory, such as the arrival on Svalbard in 1596 of Dutch navigator Willem Barentsz and the expansion of the Māori to New Zealand about a millennium ago. Like most human spread to new territory, nearly all claims of terra nullius in recent centuries have taken place under the mandate of an existing power and governance system, rather than as an autonomous experiment.

Here I use “tools” in a very general sense, which includes ideas (e.g. new mechanism design results, such as quadratic voting).

This includes institutions founded recently but closely modeled on older ones, such as the slew of governments formed during the 20th century and based on established presidential or parliamentary systems such as those of the US and UK (as well as a few based on the Soviet model). For an interesting analysis of such historical influence, see here.

True autonomy is probably a bit of a stretch, but even a more plausible scenario would likely include some degree of independence given the challenges of governing Mars from Earth: at the planets’ closest point (around 34 million miles), light – an upper bound on communication speed – takes three minutes to transit; at their farthest (just under 250 million miles), this becomes more than 20 minutes. The movement of people and physical goods would take months.

Planned topics include: the governance implications of privacy-preserving machine learning; the use of AI for institutional design; the pros and cons of representing laws as embedding vectors; information-theoretic comparison of governance systems; how interpretability research could facilitate new approaches to reflective equilibrium; and the relationship between machine learning, aesthetics and moral epistemology.

This ratio is an imperfect heuristic for accountability: there are plenty of ways that increased opportunities for popular oversight can paralyze development, exhaust voters and/or become captured by special interests. The idea isn’t that all forms of public oversight are good, or that increasing such oversight improves outcomes monotonically. A big takeaway from lots of AI safety research (as well as critiques of capitalism) is that optimizing for an imperfect proxy of what you want is a bad idea. The ratio of popular sovereignty to state capacity is just one lens among many, and I use it as an illustration of historical shifts in governance, not a definitive target for improvement.

A future essay in this series will discuss this “scalable nuance” framing in more general terms and relate it to aesthetics, philosophy of science, moral epistemology, and James C. Scott’s notion of legibility.

The next essay in this series will draw parallels between these governance tools and representations used in other domains, including scientific and moral theories.

At least I don’t expect purely technical fixes based on current R&D paradigms. For instance, rapid progress in some non-ML domains of AI might reduce interpretability issues, but this doesn’t seem likely.

Relatedly, the brief historical context I offer in the next section (“Current shortcomings”) focuses on technological constraints that limited the design of today’s systems, but clearly those weren’t the only relevant factors.